It's a BARBIE World

Dear readers - we have been thinking about opening up the newsletter to feature strong, original voices writing on tech in India as well as co-writing pieces with them.

Our latest is a guest post co-authored by Anmol and Anshul on the rise of a new founder archetype in India and their outsized impact on the Indian ecosystem.

Anshul Bhide is an active angel investor in startups along the US-India corridor, especially in AI and dev tools. He is also President at Calsoft and was previously India Head for Replit. You can learn more at www.anshulbhide.com

What is a Barbie?

In the Indian startup ecosystem, you constantly hear about how IITs and BITS produce some incredible founders. Abhishek Goyal, founder of Tracxn, said that his entire sourcing strategy during his time at Accel was going through each IIT Delhi batch - something he adopted after sourcing the Flipkart investment for the firm.

But there is a large cohort of founders in the ecosystem that doesn’t get as much airtime and that has a higher incidence rate of unicorn creation than any single IIT. These are what we call BARBIE founders - founders who did their Bachelors Abroad and Returned to Build in the Indian Ecosystem (the credit for coining this term goes to Sajith Pai, a Partner at Blume Ventures).

From Peyush Bansal (Lenskart x McGill University) to Aadit Palicha (Zepto x Stanford University), we’ve seen hundreds of these founders move back to India to build audacious, ambitious and enduring businesses in the country.

3.7%1 of Barbie founders have gone on to build unicorns, a statistic that is noticeably higher than the original IITs with 2.7% (IIT Delhi), 2.0% (IIT Bombay), 2.1% (IIT Kanpur) and 1.6% (IIT Madras)2. This cohort of roughly 300 founders creates a disproportionate amount of value in the ecosystem. The numbers speak for themselves - Barbie founders have started 11.5% of all active unicorns in the country.3

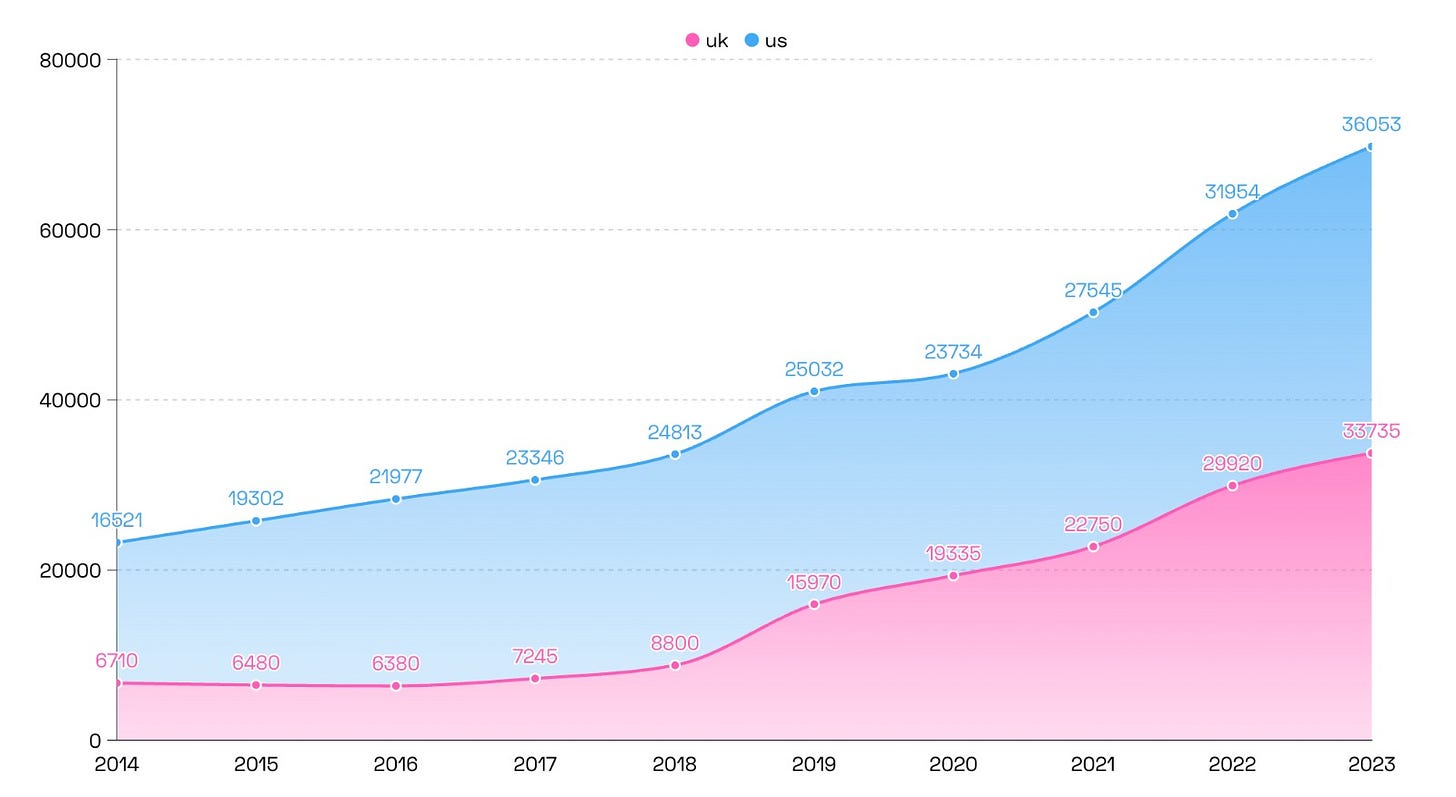

In 2024, there were 70,000 Indian students studying for undergraduate degrees in the US and UK, compared to 20,000 students a decade ago. This is a tiny minority of the overall Indian undergrad population of 33M students but this number has been growing fast. With rising income levels in India and a myriad of problems with the Indian college experience, more students are looking abroad earlier in their educational life.

Akshay, founder of Leverage - a global study abroad platform - adds, “As India’s middle class earns more and has become more aspirational, we are seeing more parents put their children through schools with alternative education boards like IB and GCSE. These students are geared towards studying abroad as they aren’t fit for applying to most universities in the country. Broadly when you also look at the curriculum abroad for undergraduate degrees, it is far superior to what is being offered in India and why we are also seeing continued tailwinds for the sector.”

Much has been written about brain drain and reverse brain drain, but there is no reliable data showing which way the trend is moving. Anecdotally, return rates among Indian undergraduates appear to be at par with, or slightly higher than, earlier cohorts, likely influenced by recent geopolitical concerns.

What do Barbies build?

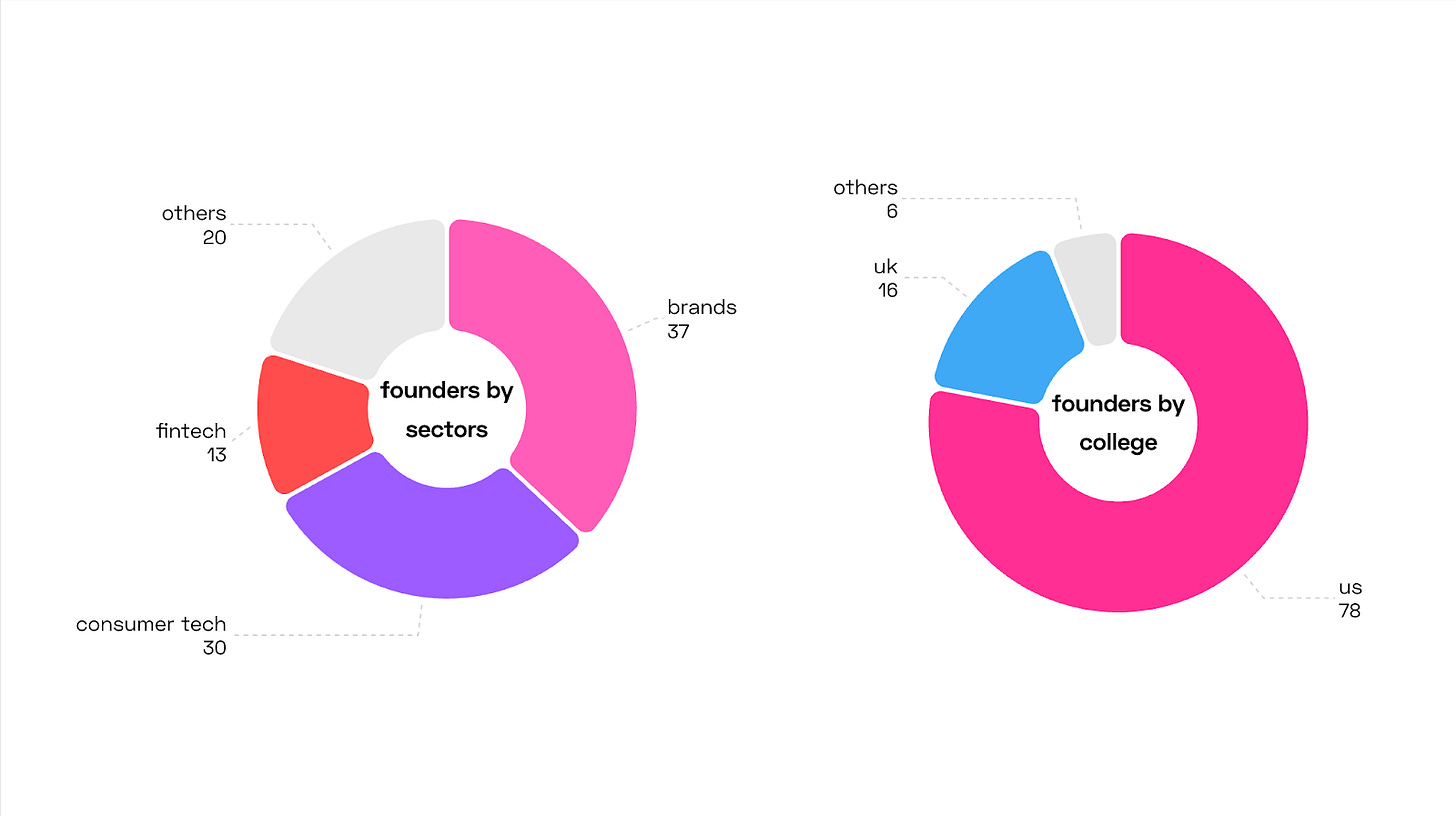

Barbies overwhelmingly build companies targeted towards consumers rather than enterprises - be it brands (e.g. The Pant Project), marketplaces (e.g. Zepto), gaming (e.g. Dream11), fintech (e.g. Upstox) or a multitude of other consumer internet businesses (e.g. Shaadi.com). The majority of Barbie founders have studied in the US (78%) which seems fitting given how America values and instills entrepreneurship.

The path of the average Barbie founder is to spend 3 to 4 years studying for their undergraduate degree, work in the country for a couple of years in tech, consulting, or banking before eventually moving back to India. A lot of these founders start up soon after moving back, but a fair number of them also spend some time working in the ecosystem or their family businesses before venturing out on their own.

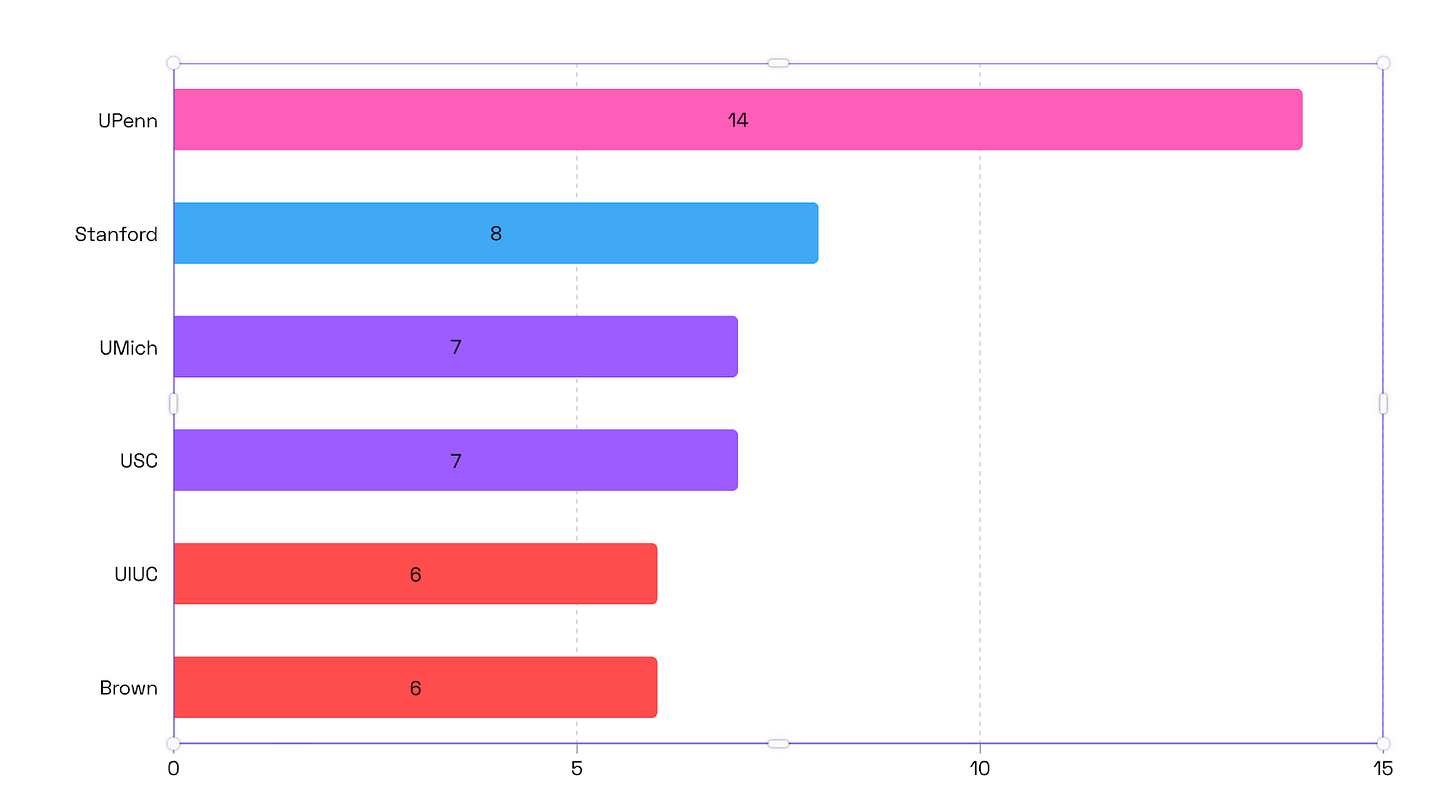

We tracked the undergraduate alma maters of Barbie founders. Penn ranks first, followed by Stanford, Michigan, and USC. Penn’s lead is unsurprising given Wharton’s presence and its role as an early cradle of US D2C, producing companies like Warby Parker, Bonobos, and Harry’s. In India, the Penn diaspora has gone on to build brands such as Knya, Taali Foods, and The Pant Project.

Abhijeet Kaji, founder of Knya, observes, “What my time at Penn and Stanford really changed was my relationship with time and ambition. I saw founders and operators who were not in a hurry to “win” a year, but very intentional about building something that would matter in ten or twenty years. That long-term orientation changes the kinds of decisions you make … and how much you are willing to invest before the outcomes are visible.”

Importantly, Kaji is clear that the value from Penn and Stanford was not purely transactional. “It didn’t directly help us hire people in India, scale manufacturing, or open stores. Where it helped was in shaping how I evaluate problems and opportunities. Being around people building globally relevant companies expands your internal benchmark of what ‘good’ looks like. You stop optimizing for incremental improvement and start thinking in larger arcs.”

The most popular sector that Barbies start up in is in the consumer brand space. This sector alone accounts for 37% of all Barbie founded companies. Founders who are building for enterprises tend to just stay back in the US as it is the largest B2B market worldwide.

As Sandeep Singhal, founder of Nexus Venture Partners, puts it,

“US returnees are more likely to focus on consumer/fintech, where they have interacted with offerings while in the US. The US undergrads who have worked in tech/science in university labs or internships, or even post-graduation in companies, tend to stay on in the US rather than come back to build in India.”

There are two key reasons for why Barbies start consumer brands: Firstly, this cohort of founders tends to develop better taste due to global exposure. These founders go to colleges in the US and UK that happen to be a melting pot for cultures. New consumer trends naturally emerge from these cultural hotspots and Barbies are then able to bring this novel flavor of products with a local twist back to India.

There is also a greater focus and appreciation on design language in many of these brands—evident in how founders often come from fashion, design, or creative backgrounds—enabling them to build brands that feel globally fluent but are distinctively India-first.

Secondly, this cohort of founders tends to belong to family businesses catering to the same or adjacent sector. Trying to build a new consumer brand is hard in India because of the lower barriers of entry of starting one leading to intense competition. These founders have an unfair advantage in building these businesses by leveraging their families’ businesses on either the supply (e.g. a textiles manufacturing family business for a D2C brand) or demand side (e.g. a family-owned retail chain or distributor that becomes the first large buyer).

Vanshika Kaji, founder of Knya and someone who is a fourth generation entrepreneur in textiles, adds,

“A family background in textiles, didn’t just give me familiarity - it gave me intuition for product and a very practical sense of how things get made. At Knya, that mattered. We could build proprietary blends early, iterate faster with mills, reduce sampling errors, and insist on the finishes we wanted to get both performance and touch right…The family business didn’t dictate what I would build, but it absolutely compressed the learning curve. It demystified manufacturing and gave us the confidence to be product-first from day one, instead of outsourcing the difficult decisions.”

Barbies’ unfair advantages

Let’s also address the elephant in the room - privilege. An undergraduate degree in the US or UK can cost up to Rs. 2.5 Cr for a 4-year program, so it is only affluent families who can afford to send their children abroad. And with affluent families (and family businesses in many cases), these founders have a safety net that often influences their decision to come back and take the risk of starting a business.

Because of the inherent privilege Barbie founders come from, they end up being bolder in the companies they build and often end up creating new markets.

Pratham Mittal, founder of Tetr and Masters’ Union, whose parents founded Lovely Professional University (LPU), expands on the role of family businesses in inspiring audacious new ventures:

“Lovely Professional University (LPU) showed me scale without elitism. It showed me what happens when you don’t over-romanticize scarcity. Massive execution, relentless expansion, systems that work at volume. That stays with you. Family businesses create a similar mental model. When you grow up seeing capital recycled, risk managed over decades, and failure treated as feedback rather than catastrophe, your risk calculus changes. You don’t confuse boldness with recklessness, but you also don’t confuse safety with stagnation.”

In addition, a lot of these businesses could only be created by founders who spent time outside the country and ecosystem because they have new ways of thinking about how to challenge the status quo and existing biases.

Harsh Jain (Dream11 x UPenn) single-handedly created a fantasy sports ecosystem in the country by having faith that the market would eventually be ready for such a product. Aadit Palicha and Kaivalya Vohra (Zepto x Stanford) showed consumers that you can build an ecommerce marketplace from scratch and deliver products to millions of customers within 10 minutes. Anjali Sardana (Pronto x Georgetown) is transforming home services by organizing a fragmented workforce with professional standards and dignity to deliver a level of reliability and consumer delight previously unseen in the country.

Anjali Sardana, founder of Pronto, articulates this dynamic clearly:

“An industry that hasn’t been cracked before requires new solutions. Founders who have been a part of the ecosystem tend to fall back on priors or their biases while attempting to solve problems. But not being part of the system helps you tackle challenges using first principles thinking. It allows you to design solutions that may seem counter-intuitive to the rest of the ecosystem but ultimately work better.“

For Anjali, this advantage was directly shaped by her time at Georgetown, where the liberal arts college experience exposed her to diverse perspectives that forced her to constantly challenge her assumptions—an approach she credits as essential to building Pronto.

Barbie founders also excel at fundraising. This is a result of having access to unique networks and a liberal arts undergrad background embedded in curriculums abroad. For example, Penn undergrads have access to Penn alumni that dominate both the founder ecosystem and the investor ecosystem. Colleges abroad encourage a healthy dose of interdisciplinary liberal arts classes with all the critical reading and writing training that goes with it. As a result, Barbies are able to articulate their startup vision with clarity. As a founder, you are selling to everyone - early employees, investors, and clients. In the early days of a startup when you have nothing but a story, the most creative storytellers are the ones that succeed.

However, it isn’t all rosy for these founders. They have no access to the IIT / BITS networks that are omnipresent in the Indian startup ecosystem. And coming from predominantly English-speaking privileged backgrounds sometimes works against them as they might have real blind spots about how the long tail of India lives and consumes. This is why you might not see a Kuku FM or Meesho being founded by a Barbie founder. Finally, some investors are biased against this cohort of founders, viewing them as less hungry because they come from privilege - which can be a fair argument.

Do VCs back Barbies?

In most multi-stage venture firms and sector agnostic firms, only 3-5% of the founders are Barbies. They aren’t able to back as many Barbie founders for a couple of different reasons - 1) there aren’t a huge number of Barbie founders so while a firm might be able to back a couple Barbie founders every year at most, they might end up investing in 10 to 20 companies a year; 2) a lot of multi-stage venture firms do not invest in consumer brands as the outcome sizes are too small to return their funds and thus a majority of Barbies couldn’t raise capital from them in the first place.

At Untitled Ventures, we love backing Barbie founders because 1) both of us (Anmol and Vedica) also studied outside India and naturally we know and relate with a lot of these founders. We’ve invested in Hena Mehta’s company Basis (Vedica’s classmate from Wharton) and Zefaan Kanwar’s company XTCY (Anmol’s classmate from high school); 2) we love investing in consumer businesses and brands that have taste and we think Barbie founders best exemplify that. We back the most Barbie founders in India at 25% of our portfolio - 6x the rate of the average venture capital firm.

The future of Barbies

Indians were able to study and immigrate abroad over the last 30 years during the heyday of the global economy and globalization. While there are increasing headwinds for global immigration, countries are still eager for international students and Indian students are yearning to study abroad. But the political environment in these countries discourages them from staying on after they graduate.

There has never been a brighter time to build in India. The last decade has produced battle-hardened product & engineering talent that has seen large systems operating at scale at companies like Zomato and Flipkart. India’s annual GDP growth is the highest amongst the large economies, growing at 6% to 7%. Finally, there is a surplus of VC funding available to back bold founders.

As a result of all this, Barbies are more likely than ever to move back to India and build. Combined with an increasing number of Indians choosing to study abroad in the first place, we anticipate the number and significance of Barbie founders will increase significantly in the coming years!

As a final callout, Anmol also co-hosts a monthly dinner series across Delhi, Bombay and Bengaluru for founders, investors and operators in the Indian ecosystem who have moved back to India from the US. Check out and join 1291 club if you’d like to attend a future dinner - there are upcoming dinners in Bengaluru (Jan) and Bombay (Feb)!

Appendix

Thanks to the countless people that we spoke to while writing this - we really appreciate your time and thoughts. If you’d like to see the full non-exhaustive list of Barbie founders that we are tracking check it out here. If you think that there’s someone missing from the list, you can request to add here.

There are roughly up to 300 Barbie founders in India, 11 of whom run companies worth $1B+. We have a non-exhaustive list here

Retrieved from Rest of World’s piece on IIT founders.

There are 11 unicorns started by Barbies worth $1B+. There are 95 active unicorns in India.

Good piece, Anmol and Anshul. Ofc I am biased but still!

We’re at the start of the BARBIE going after deep-tech as well and often choosing to not go/drop-out of college entirely. Not yet unicorns but give them time. Though I wouldn’t make claims of them doing better than other founders inherently

Praan, Airbound, Aspera, Jhana, and i’ll be self serving and add Dognosis as well ;)